This is the Work

A slide deck summary of key activities delivered jointly by Bond and Peace Direct considering how to apply anti-racist and decolonial approaches to policy and advocacy work

Contents

1. Summary of key points raised in conversations with advocates from low- and middle-income countries and UK diaspora groups

The project began with a set of interviews with people working in policy and advocacy roles in low- and middle-income countries and/or from UK diaspora communities and organisations.

In November 2023, The Advocacy Team conducted five in-depth interviews. The interviews were designed to hear perspectives on the extent to which the UK development sector has adopted anti-racist or decolonial approaches in their work and the measures they could take to go further. We are grateful to the participants for the rich insights provided.

How does current policy and advocacy work (as currently applied) uphold racist or colonial systems and approaches?

- Power and privilege are pervasive across policy spaces.

- There is a general failure to acknowledge the history of colonialism, slavery and occupation, and the way this history continues to contribute to global inequities, inform policies and systems and the way ‘business is done’.

- Similar failure to integrate this history in the analysis of the causes of poverty and inequality.

- Policy and advocacy professionals set the agenda; they determine what causes to champion and how – but who are they accountable to?

- Certain high-income countries are seen as the ‘benchmark’ to aspire to with respect to knowledge and expertise, including in advocacy and campaigning.

- A preference for terms such as ‘socioeconomic’, ‘marginalised’ etc., instead of calling out structural inequalities and their causes. A failure to challenge the language that government uses on race.

- The pace of reform is too slow. There have already been workshops, strategies and commitments but these are not applied in practice.

It boils down to commitment – there is no sincere commitment as it will mean people reconciling with racist and colonial history and I don’t think anyone is ready to be doing that.

– Interviewee

What measures can policy and advocacy professionals take to address the issues identified?

Challenge unequal power relations in the UK civil service, especially in key policy forums where we wield influence, presenting clear evidence of the lack of minority and working class representations at the top of the civil service.

Include new voices to advocate for more ‘radical’ policies, which challenge the status-quo and ways of thinking.

Invest in data to address evidence gaps, making it easier to challenge inequities.

Introduce cultural changes in the approach to engaging with communities, moving from consultation to genuine partnerships.

Ensure that impacted communities drive, or at a minimum should co-design, global advocacy campaigns.

Commit to applying actions that come out of consultation and be transparent about progress.

Impacted people and communities must also be the messengers of change. Consider ways to bring them into the room with stakeholders, policymakers and in decision-making conversations.

Are there any changes needed at the organisational/sectoral level?

- Acknowledge structural racism, and connect existing initiatives to challenge internal and external inequities.

- Engage in work that is community led – have an open, public dialogue – and consider how this translates into change at a national or regional level.

- Be open to challenging the government. Too often, NGOs have an organisational agenda and are not as critical of the government as they should be.

- Connect this agenda to everyday work.

"We need to decolonise our mind… Colonisation comes because [of] thoughts that [what] those from the west think are best. What needs to change, and who is doing the messaging around the advocacy, who is the messenger, even where and how the advocacy is happening, has to be led from different contexts within issues. European issue: European countries should lead. The process should be led by the country with the issue." - Interviewee

Connecting the work of advocates and campaigners with neo-colonialism

As advocates, does our work seek to ‘control’ government policies in low- and middle-income countries or international policies that affect these countries?

Do we directly or indirectly use financial resources to influence or ‘dictate’ policies?

How do we know the consequences of the policies we advocate for? What if these policies have negative consequences, who are we accountable to?

“Neo-colonialist control is exercised economically. The Neo-colonial State may be obliged to take the manufactured products of the imperialist power to the exclusion of competing products from elsewhere. Control over government policy in the Neo-colonial State may be secured by payments towards the cost of running the State, through civil servants who can dictate policy, and monetary control over foreign exchange through the imposition of a banking system controlled by the imperial power.”

- Kwame Nkrumah

2. Findings from barriers in policy and advocacy survey

Following a consultation with the working group, members said they would find it helpful to understand the barriers that prevent policy and advocacy staff from adopting anti-racist and decolonial ways of working.

Accordingly, a survey was designed to understand the perspectives and experiences of policy and advocacy staff working at every level in development and peacebuilding organisations.

In total, 40 policy and advocacy staff members completed the survey.

Key findings

The majority of respondents were female (68%) and white (83%). Consequently, the demographics of people who participated in the barriers survey was in contrast to the group who participated in the initial round of consultations from low- and middle-income countries and diaspora organisations. The perceptions of how the two groups see progress in adopting anti-racist and decolonial frameworks were very different, where overall respondents to the survey were positive about the progress to date.

TOTAL RESPONSES: 40

Most respondents (68%) think their organisation is actively working to address or reverse the historic and unequal power dynamics that exist in policy, advocacy and research work.

Most respondents (75%) felt they have the knowledge and tools to apply anti-racist, decolonial approaches to their work. However, they also highlighted the need for more support on the implementation of these approaches.

Most respondents noted they have actively spoken to policymakers about anti-racism, decolonisation or similar issues. However, the majority of respondents also felt pushback from peers in the INGO sector to them speaking about these issues due to fear of losing influence or engagement with political targets.

Respondents are looking for clearer guidance, internal support and buy-in, greater leadership engagement and financial support to effectively implement these practices internally and to effectively discuss these issues in their policy and advocacy work more broadly, particularly when engaging with political stakeholders or big INGOs.

Additionally, many respondents called for improved sector-wide coordination on this work and more networks and support structures for organisations to exchange knowledge, models and experiences in applying these practices.

Despite progress, some respondents expressed concerns that there is a loss of momentum in interest in this work, or it is being deprioritised by issues that are more aligned with government stakeholders, and emphasised the need for continued dialogue and action at all levels of the sector.

Summary of respondent background

Gender breakdown of respondents

Organisation size

* Small (10-49) 27.5%, Micro (Below 10) 12.5%

Ethnicity breakdown of respondents

Breakdown of non-white participants by ethnicity

- 7.5% Black and Black British

- 5.0% Asian and Asian British

- 2.5% Mixed or Multiple

- 2.5% Other ethnic group

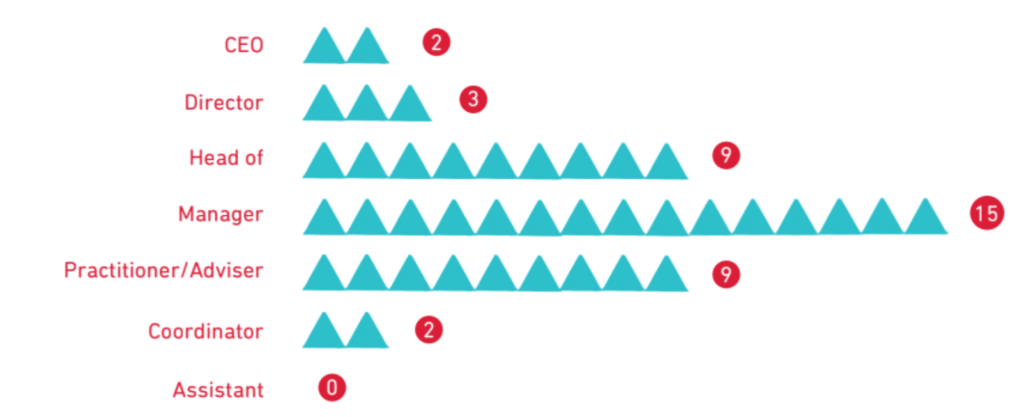

Level of seniority of respondents

- The majority of respondents identified as female and were white (mainly English / Welsh / Scottish / Northern Irish / British).

- Most respondents were middle to senior management, either a practitioner / adviser, manager or head of level.

- 47.5% of respondent organisations were small and medium and 40% were from large organisations.

Main barriers respondents personally faced in their career in policy and advocacy

- Recruitment - 10

- Education - 6

- Knowledge and expertise devalued as a POC/or from Global South - 4

- Communication devalued when it deviates from normative notions of whiteness - 7

- Ongoing challenges to authority and legitimacy - 8

- Being told that you were not a ‘good fit’ for the organisation -5

- Visa sponsorships - 4

- Microaggressions - 11

- Lack of opportunities for promotions/progression - 22

- Micromanagement - 17

- Work culture and lack of inclusion - 13

- Occupational segregation - 5

- Other - 9

Top barriers:

- Lack of opportunities for promotions / progression

- Micromanagement

- Work culture

- Lack of inclusion

Other barriers included:

- Not faced any (some citing because they were white)

- Lack of understanding of, and discrimination against, disability, class, sexual orientation, language differences

- Being too outspoken in a manner that was considered politically sensitive

Do respondents feel their organisation is actively working to address or reverse the historic and unequal power dynamics that exist in policy, advocacy and research work?

- Most respondents think their organisation is actively working on this.

- 23% of respondents were unsure if their organisation was doing so.

Do respondents feel they have the knowledge and tools to apply anti-racist, decolonial approaches to their work?

- Most respondents felt they had the knowledge and tools to apply anti-racist, decolonial approaches to their work. They also felt they had support from their organisations and managers to apply these new frameworks or approaches.

- The qualitative responses highlighted the complexities and challenges associated with implementing these approaches in policy and advocacy work, underscoring the importance of ongoing support, organisational commitment, and systemic changes to effectively address these issues.

“I have the tools and knowledge, but there is resistance in these being applied in the workplace.”

“I have some knowledge and support but not enough time to digest a wider range of policies to implement that learning well enough.”

Do respondents feel they have the knowledge and tools to apply anti-racist, decolonial approaches to their work?

More focus on implementation is needed and organisational resistance is ongoing:

Most respondents felt they had a foundational knowledge of these practices but needed more support beyond diversity, equity and inclusion training and sessions around anti-racism and decolonisation. Respondents also described internal challenges which continue to prevail that actively made it difficult to apply anti-racist and decolonial principles in their day-to-day work. This includes difficulties in reforming internal processes and decision-making systems. There needs to be more support in practical implementation and ongoing learning.

More actionable changes:

There is a desire for more tangible changes in organisational processes and practices to align with anti-racist principles. This includes reevaluating accountability structures, “valuing local knowledge and co-creating new research”, and centring the voices of underrepresented groups in policy spaces.

Ongoing learning and improvement:

Respondents emphasised that the journey towards anti-racism and decolonisation is ongoing and requires continuous learning, unlearning and active effort, both at the individual and organisational levels. Some respondents felt their organisations were doing better by taking an intersectional approach and transferring power in partnerships, for instance.

Have respondents spoken to policymakers about anti-racism, decolonisation or similar issues?

Respondents noted experiencing pushback internally, particularly on external communication and engagement. For example:

- In wider advocacy initiatives.

- At the decision-making point for a communications product (e.g. what should be included in a sector manifesto)

53% of respondents also felt pushback from peers in the INGO sector to them speaking about these issues.

Other organisational challenges included:

- White colleagues not feeling comfortable in engaging in conversations about anti-racism.

- Facing pushback further up within an organisation due to these changes being seen as ‘impractical’ or not the most effective use of money and resources.

- External: Nervousness internally about organisational perception externally, particularly in relation to government engagement. On this specifically, respondents have noted mixed responses. Some engagement was seen as positive, depending who they were engaging with. But this positive response was either made in private only, or with no meaningful follow-up or real clarity on what practically comes next.

- Internal: Within their organisations, they noted disagreements on how to frame decolonisation in ways that will influence political targets, or the sense that it would not ‘land’ well with planned political targets more generally. Overall, respondents did not feel this was prioritised as an agenda, noting it has been considered ‘disruptive’ or too ‘radical’, rather than realistic, for the political climate we are operating in.

“I have had feedback that we should be focusing on core issues such as tackling global poverty rather than what they perceive as these ‘around the edge’ issues.”

“Being unable to challenge the discourse from an anti-racist lens, or challenging the way parliamentarians frame it, for fear of losing their engagement.”

What are respondents finding most difficult about applying these approaches?

Internal resistance and buy-in:

Many respondents face challenges in garnering support and buy-in from colleagues and senior management to adopt these approaches within their organisations. There is reluctance to reflect on how racism manifests within the team’s dynamics and the organisation’s position of power.

External pressures and priorities:

Respondents, particularly those higher up in the organisation, face external pressures, such as conflicting priorities, funding restraints and a focus on immediate needs which deprioritises long-term transformative change.

Language and communication:

There is difficulty in finding appropriate language and communication strategies that resonate with various stakeholders while staying true to anti-racist and decolonial approaches. Disagreements on language and definitions risk being more politically charged.

Capacity and resources:

Limited resources, both in terms of time and funding, pose challenges to embedding anti-racist decolonial approaches into all aspects of policy and advocacy work. There is a noted need for dedicated resources and prioritisation to support this work, particularly to pilot new ways of thinking, for instance.

Political constraints and fear of backlash:

Engaging with policymakers from different ends of the political spectrum presents challenges due to fears of backlash or loss of influence. There is hesitation to discuss these issues out of fear of being labelled as too activist or risking relationships with government stakeholders more broadly.

“Getting internal culture to embrace a truly decolonial and locally-lead approach to programming.”

“Lack of qualitative metrics shared across organisations that can be used to measure real change.”

“It is seen as something additional rather than something that is fundamental to our work.”

What are respondents finding most difficult about applying these approaches?

When engaging with others, particularly government, respondents noted fear about talking about these issues with a Conservative government and a fear that it is not a priority for Labour, so they prioritise other issues. They have also faced pushback from larger INGOs and have risked being deemed ‘too activist’ when bringing in such discourses. Respondents also noted a nervousness that, should governments adopt this language, it risks being misused.

Respondents also noted that getting buy-in from the wider sector is challenging. The sector also works with a range of organisations that do not all have the same policies and understandings of these approaches. Applying these approaches to organisations outside the UK can also be challenging.

“There is so much fear that the government / policymakers would not engage with us when I don’t think that is really the case, and it hasn’t even really been tried by so many NGOs.”

“The expectations of feasibility when connecting with policymakers from political parties across the spectrum unable to utter the word colonialism, let alone grappling with it"

“There is an ingrained conservatism in much of the sector, which often prevails despite recent professed commitments to anti-racism and decolonisation.”

Where respondents are applying anti-racist, decolonial approaches:

- Collecting and analysing data

- Strategic planning

- Day-to-day advocacy and planning work

- Project evaluations

Others ways anti-racist, decolonial approaches are applied included:

- Directly funding grassroots organisations in low- and middle-income countries

- Policy language

- Events

- None of the above: some reasons shared - because we are figuring out what it means, or we are thinking about how it can be embedded into our strategy, or we are heavily responding to donor requirements rather than decolonisation, or we have an anti-racist approach to our communications but it doesn’t inform our day-to-day work

Many note a desire to do this within their teams and organisations, and many are in the early stages of doing so. Others are further ahead in thinking about how they partner with stakeholders in low- and middle-income countries. Other examples included developing inclusive learning frameworks, redesigning monitoring, evaluation and learning data collection and redesigning policy and advocacy strategies.

What would be helpful to better apply these approaches?

An analysis of the survey responses found that the following would help apply these approaches internally:

Having the ability to scrutinise internally and consider different approaches that could disrupt the original model of working. At the same time, being realistic about what can be done.

In-depth discussions and collaboration:

Long-term discussions to explore how racism and colonialism intersect with policy structures and thinking about the social backgrounds of the people we work with and work for, and linking this all with practical applications of anti-racist, decolonial approaches. These conversations could be had within a safe space for sharing and learning to enable honest sharing of barriers, best practice and strategies which could drive real change within organisations, for instance.

Greater engagement from leadership:

Encouragement from senior leadership, including CEOs and directors, to actively participate in discussions, discuss initiatives and how they apply these practices, and demonstrate a commitment to allyship.

Financial support:

Recognising the need for financial resources to support initiatives aimed at learning about and implementing anti-racist, decolonial approaches and practices.

Toolkits and FAQs:

Providing toolkits and FAQs on effective actions, internal advocacy and engaging policymakers on decolonisation.

“Clarify the approaches; be clear on actions and outcomes. Recognition that not every initiative will be successful.”

“Troubleshooting messages that can be applied against the usual kind of pushback and application of sector commitments.”

Guides, examples and checklists:

Providing examples of good practices, checklists and commitments from the entire sector to illustrate how to implement anti-racist, decolonial approaches.

Networks and support structures:

Establishing strong networks and support structures for individuals and organisations to exchange experiences, seek advice and collaborate effectively. This could include models and guidance from similar organisations. A few suggested examples include training and peer groups, a private network, an advisory board / steer community.

Improving coordination and alignment:

across the sector to create unified advocacy efforts and stakeholder engagement.

Clear understanding and communication:

Continuous dialogue across all levels of the sector to clarify the concepts and practices of decolonial, anti-racist approaches and provide practical guidance and strategies.

Address the UK’s colonial legacy:

Acknowledging and addressing the UK’s colonial history and its impact on how the sector is set up and operates including “national policy-change processes”.

“Realistic guides with alternative approaches - like the language guide by Bond and another by OXFAM.”

“Facilitated dialogue with the more conservative parts of the sector around the areas of disagreement. Without this, we will likely continue to push in different directions and undermine each other.”

3. Summary of key points from the discussion with policymakers

In March 2024, Bond and Peace Direct’s members organised a discussion with three current and former policymakers from across the political spectrum on how to apply anti-racist and decolonial approaches to their work. The session was held under Chatham House rules so only a high-level summary of the key points can be provided.

Participants in the roundtable discussion raised a number of important discussion points:

- It is important and necessary to review the model of how NGOs in high-income countries and the NGO sector overall operates, and deal head on with the perceptions some entrenched ways of working could be part of the problem, impeding sustainable development.

- The limitations of simply using the rhetoric of decolonisation, and the need for organisations and policy and advocacy staff to connect the rhetoric to what practical changes must emerge from this agenda. For example, NGOs present were challenged to consider the implications of ‘working ourselves out of a job’. Genuine shifts in power will be uncomfortable. A long-term perspective is needed.

- There is competition among the NGO sector around decolonising aid. But the sector is still holding funds and resources in a way that impacts how people are able to operate locally. ‘White saviour’ mentality is still prevalent in the sector. For advocacy, there’s a problem with asking politicians for things we are not doing ourselves.

- Engaging with politicians: One panellist stated that ministers don’t have much experience but think they do. We should expect them to listen, learn and treat counterparts in low- and middle-income countries as equals - but the reality is British ministers haven’t done that. Key is listening before speaking, with humility.

- Advice for framing issues of decolonisation: Be practical as well as using the rhetoric. For example, discuss power dynamics but link it to practical issues with the goal of influencing someone who does not think in such terms (e.g. lack of translation). To discuss these issues, for example, with politicians think tactically; we have to talk in terms that people understand and where there is relative consensus, such as repair of damage done.

- The importance of facing the world in all of its complexities, and how an evidence-informed approach should help with this effort.

- The consensus that, as difficult as this agenda is, it has the potential to contribute to strengthened and more effective development partnerships between countries that provide international development assistance and those that receive it.

- ‘Aid’ is only one part of the international system, with limited overall power. We have to consider shifting power in the wider context of international policy areas and levers (e.g. reform of the multilateral system).

- Consideration of how we educate people in the sector – too often there is a perception of international development as an ‘industry’.

- The importance of seeing the true origins of emergency situations and poverty in the present day as born of colonialism. The wealth of ‘aid providers’, including the UK, is a result of that history. We need to move away from a model of reliance to a model that works with communities.

- Discussion on the role of reparations: Shift to seeing ‘aid’ as a form of reparations (repairing damage that is done). Not revolving only around money – we should also see it as shifting institutions and providing respect/acknowledgement. Room for better partnerships with low- and middle-income countries that doesn’t involve telling them what to do. ‘Aid’ isn't the only way – role of diaspora and remittance, for example.