Building the development organisation of the future

International development organisations know they need to change to stay relevant in an accelerating world, but moving beyond platitudes to think differently about the future is not easy.

We felt it was time to deploy a new approach to help people move beyond the status quo. And so Bond, UNDP and Nesta turned to Superflux and speculative design.

Here we will attempt to explain why the four of us partnered to create a fictional development organisation “of the future”. We’ll share what we produced, and the process we went through to get there. We’ll summarise the responses this fictional organisation received, what we think people can take away from this experiment, and what we’ve learnt.

Navigate this page:

- A new approach to help people think differently about the future

- Simulating a future development organisation

- Our design process

- The reactions

- The broader implications

- What we wish we’d done differently

- What we learnt

- Now what?

A new approach to help people think differently about the future

Our unlikely partnership stemmed from recognition of a shared problem: although the external environment is changing profoundly, short-termism and risk aversion still dominate the traditional players and institutions within the development sector.

Recognition of the problem has increased; “Innovating and adapting to stay relevant in a changing context” is now the second ranked long-term priority for Bond member organisations, for example (not far behind the obviously related “diversifying funding streams and becoming financially sustainable”). But a proliferation of trends analysis, think pieces, and expensive consultancies appear to have yielded only modest change in organisational behaviour, transformation or innovation to date.

We believe traditional approaches to corporate strategy and planning are one of the major villains behind this. Relatively unchanged since the 1960s, traditional strategy approaches were designed for tackling technical challenges in stable times. They tend to plan for just one “probable” near-term future (that tends to look much like an extrapolation of today), ignoring a wider range of other ‘possible’ futures that could emerge – the very space where there is the greatest potential for business model innovation, new solutions, new revenue streams and “doing things that have never been done before”.

We felt it was time to deploy a new tactic to help people think in a less constrained way. We wanted to unleash the ability of development practitioners to think beyond the entrenched status quo, to look at the issues they and their organisations’ face from new perspectives, and come up with new solutions and ideas. Being able to imagine alternative futures and possibilities is critical to this.

And so we turned to experiential futures and Superflux. The term Experiential Futures refers to a range of approaches involving the design of situations and stuff from the future to catalyse insight and change. Our hypothesis was that by creating something tangible that people could experience and interact with, we could help bring one possible future to life – providing a bridge from abstract trends to concrete implications for today. Futurist Stuart Candy has written about our “chronically impoverished practice of public imagination.” Our collaboration was an effort to start to change that within our respective parts of the international development community.

And so working with Superflux, the three partners Bond, Nesta and UNDP embarked (with the help of some fellow travellers including Indy Johar and Clare Agar) on a mission to design a development organisation of the future.

Our intention was not to create the “optimal” organisation, or even a necessarily desirable one – but to create something that would provoke and challenge.

Simulating a future development organisation

“Mantis was born out of frustration at the inability of existing institutions and governments to deal with escalating transboundary risks. As we saw climate food, resource and political crises begin to multiply we decided a new approach was needed. We drew on our extensive expertise across neural networks engineering, systems analysis, game design, behavioural science and international development to build Mantis.” Mantis Systems pitch, February 2018

After an extensive foresight and design process (see below), we shared our simulated development organisation of the future – Mantis Systems – at the Bond Conference in February 2018.

In this hypothetical organisation, a powerful artificial intelligence (AI) integrates open source data with behavioural insights and location data to continuously model and avoid systems risks. Its unrivalled understanding of human behaviour is generated by citizens who use the “Mantis World” crisis simulation game. Real-time location data to enhance the AI’s decision-making is provided by a citizen contributor network through the Mantis App.

The purpose of Mantis Systems is to implement high impact mitigation strategies using minimal resource. Its citizen contributors carry out micro, pre-emptive interventions to collectively downgrade identified systems risks. But game players and app users also contribute their distributed computing power, which further improves the AI’s cognitive abilities.

The Mantis app directs citizens to carry out micro-challenges that contribute to the AI’s overall goal of reducing system risks. They are rewarded with Mantis cryptocurrency for successfully completing their task.

Case study 1: promoting climate resilient crops

In the first case study, Mantis tackled the issue of the vulnerability of the global food system to climate shocks. The gap between food supply and demand was predicted to double by 2050, with society at risk of total collapse. Mantis’ risk modelling algorithms identified Ethiopia as especially high-risk. The AI proposed and modelled multiple strategies to leverage influence within this highly complex system, and finally tested a “non-linear” information strategy. The AI predicted that driving global demand for climate-resilient “ancient” crops such as Sorghum (and reducing demand for resource-intensive crops such as maize and wheat) grown in Ethiopia would help change consumption globally and locally, reducing food insecurity over time.

“Fake-news-for-good”?: Mantis’ social media campaign promoted the benefits of teff and sorghum, while also generating negative publicity about maize and wheat.

Case study 2: tightening mobile money security

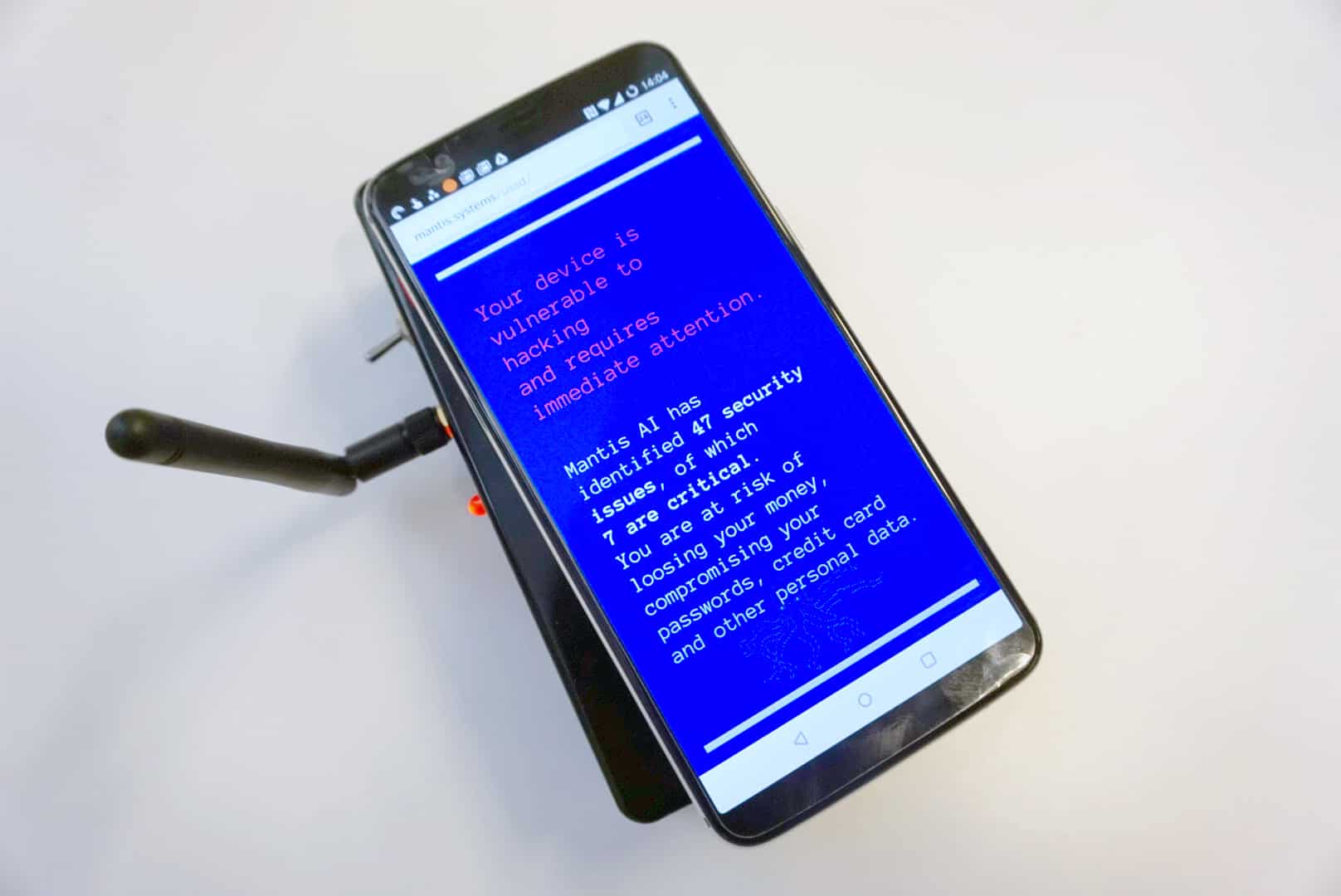

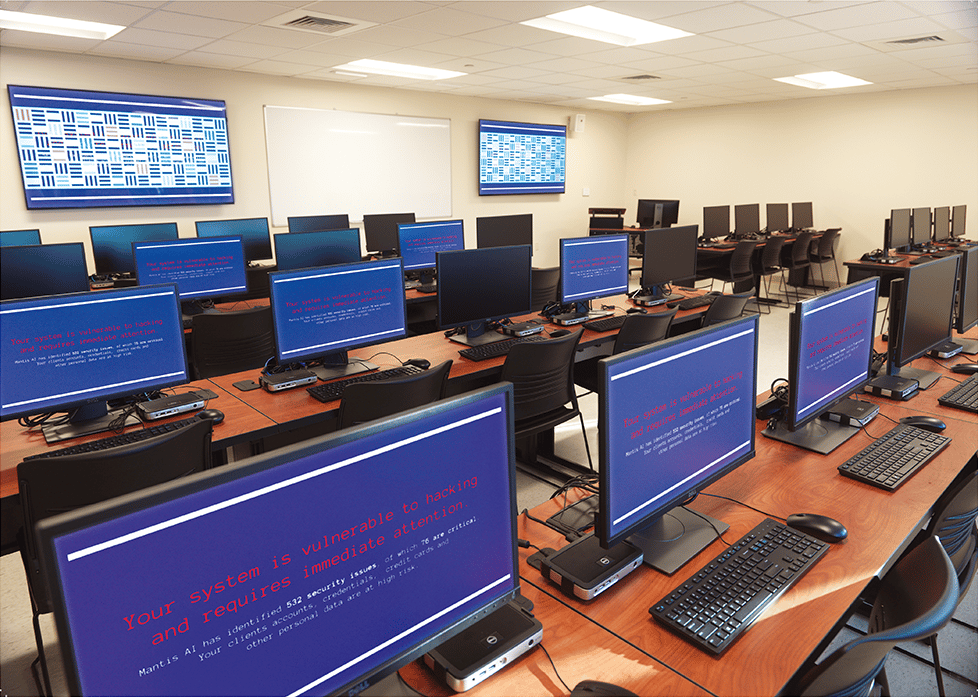

In the second case study, Mantis took on cyberattacks, a global systemic risk rising high up the agenda of the World Economic Forum and already costing Africa an estimated $2bn a year – but not yet something considered by the mainstream development community.

Mantis identified an active exploit capable of shutting down mobile money systems in Kenya – with consequences for the economy (mobile payments account for half of Kenya’s GDP) as well as people’s ability to pay for basic goods. After an unsuccessful “traditional” awareness-raising approach, Mantis simulated ransomware attacks against vulnerable mobiles – testing a variety of methods to force individuals to patch their phone’s security before the real exploit locked them out of their accounts.

Our design process

It’s worth emphasising that Mantis was our attempt to realise one potential organisation from one possible future to stimulate and provoke a longer debate. The process we went through was led by Superflux and was fairly involved. We’ve outlined the process below for anyone who might be interested in the approach used.

So, how did we arrive at Mantis?

Stage one: horizon scan and interviews

We began with a horizon scanning initiative – tracking key trends and weak signals. To bring variety to our own images of the future, we carried out some rough and ready ethnographic research to capture a wider range of views about the future – interviewing government representatives at a UNDP conference from Sri Lanka, Somalia and Nigeria, as well as other delegates from Egypt and Paraguay. We also organised a “reverse archaeology” exercise with a varied group of UNDP staff and partners.

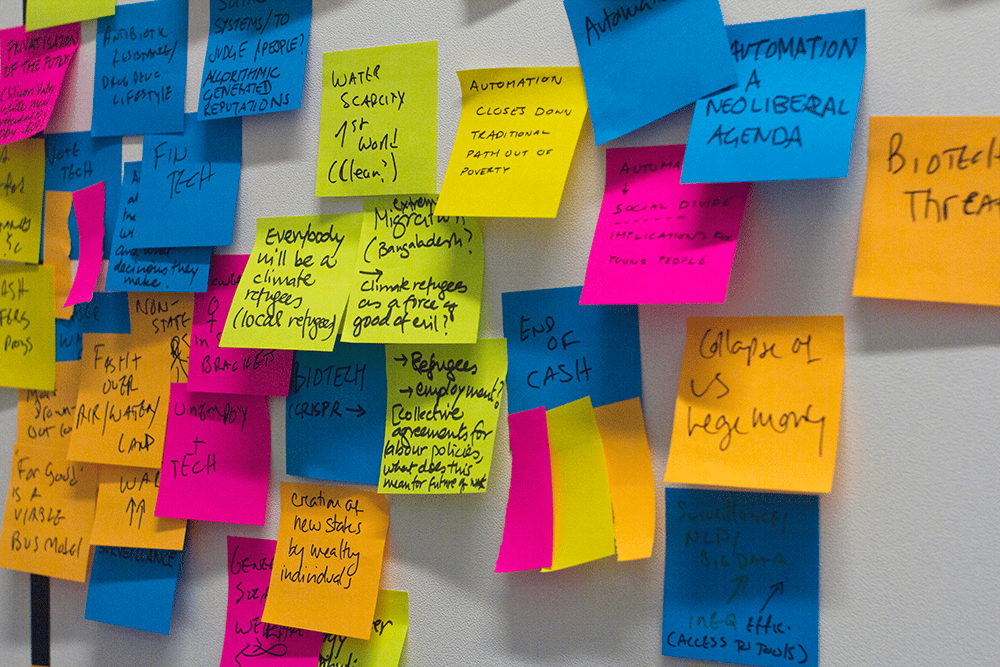

Stage two: identifying priority themes

In our first workshop together as a group of collaborators we prioritised and clustered the trends and signals that had emerged from our research (while also attempting to interrogate the personal bias we brought to that process). Five key themes emerged: 1) the changing locations and tensions of power e.g., citizen self-organising vs corporate monopolies 2) acceleration of technological advances 3) the eroding role of the nation state and multilateral cooperation 4) growing crises from climate change and resource scarcity 5) shifts in the financial system and its institutions (e.g., move away from cash) and the emergence of new business models.

Stage three: scenario generation and world building

In advance of the second workshop, we worked together to produce four scenarios [PDF] to help us think through how our identified trends could interact to produce alternative futures. We chose two key uncertainties from the above thematic clusters as our axis: power (concentrated – decentralised) and global cooperation (fragmentation – coordination). We then built up the four scenarios drawing from the horizon scanning work from stage one. These alternative futures provided a framework to move from vague ideas about the future into more specific ones. As any future is likely to contain elements of different scenarios, our world-building exercising involved combining two of our four scenarios and further shaking these up with randomly-allocated “black swan” events. From this exercise, we produced five different worlds.

Stage four: translating ideas about the future into tangible objects

Next our group began an exercise to design “development” organisations that could be operating in each of these worlds. This ideation exercise concluded day one of our workshop. The second day of our workshop was focused on narrowing down the attributes and themes we wanted this fictional development organisation to answer, which Superflux would then design around.

Table 1: consolidated key ideas for the development organisation of the future

| Organisational structure | Issues | Operations | Technology |

| Nimble, virtual, “shape-shifting”, decentralised, automated | “System-risks” e.g, climate change and resource scarcity | Proactive, anticipatory, adaptive and experimental, operating in “grey zones” of what is legal/ethical to do “what works”, leveraging alternative volunteering | New division of labour between humans and AI – exploring balance and trust issues |

Following this stage, Superflux began work on an initial design concept, which was iterated over a period of weeks in the run-up to the Bond Conference. As each part of the concept emerged (e.g., the game simulation to the cryptocurrency micro-payments), Superflux developed questions for us to build on – helping to flesh out how each component worked.

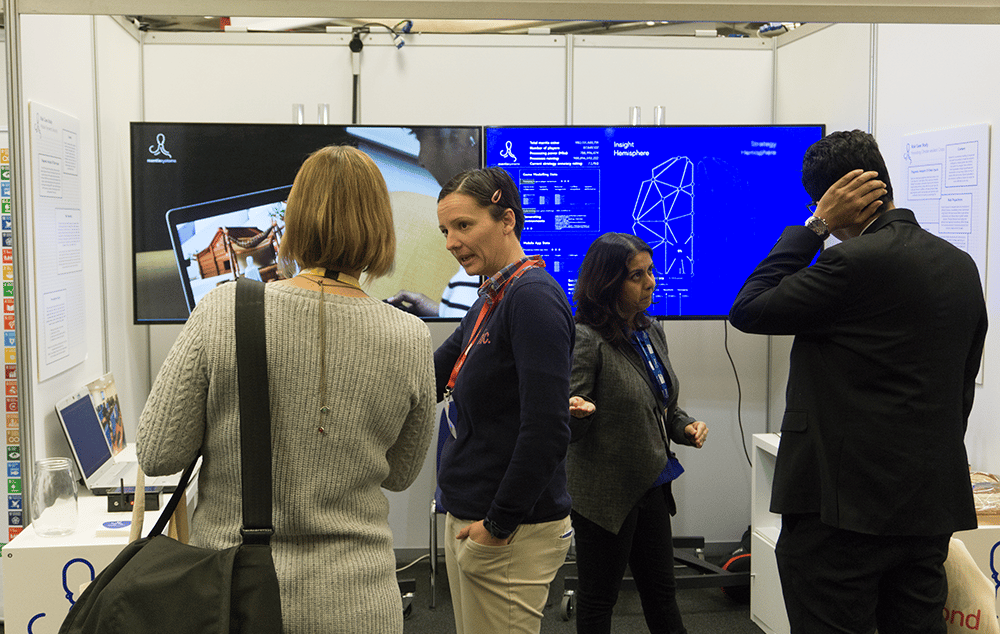

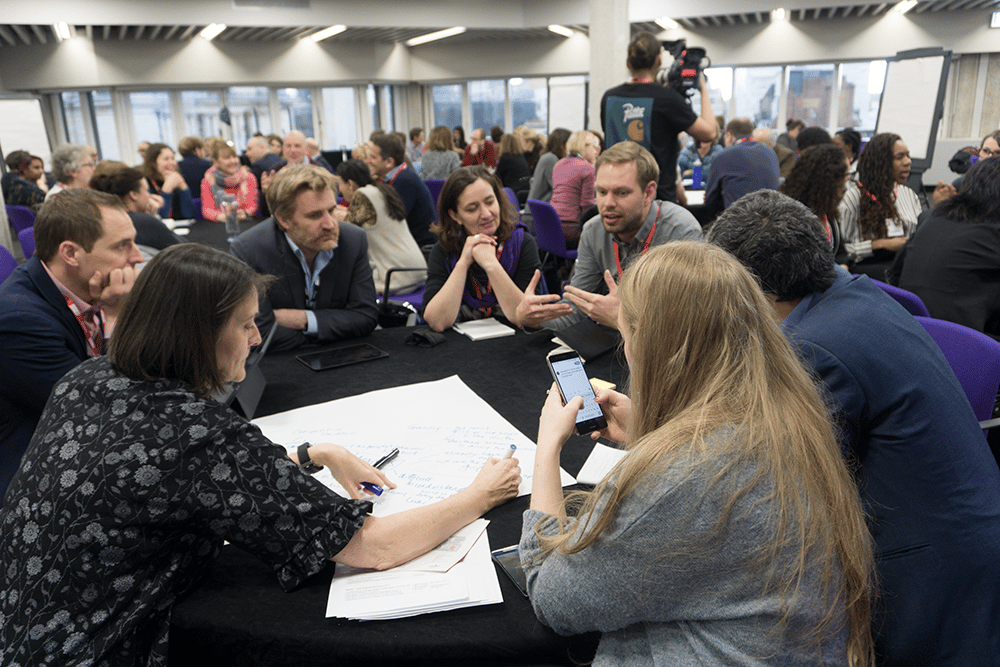

Stage five: staging the experiential future

The Bond Conference is a gathering of around a thousand development professionals from the UK and beyond over two days. To “blend in”, we took a stand in the exhibition hall, along with forty other organisations promoting their work. This provided diegetic integrity as well as the opportunity for delegates to encounter Mantis Systems during the conference breaks. The Mantis stand consisted of two screens showing two linked films – a promo video for the Mantis products and another showing how the Mantis AI operates. This was supplemented by two fictional “case studies” of how Mantis had intervened to prevent the meltdown of the mobile money system in Kenya, and to increase food security in Ethiopia. Superflux produced a number of objects to illustrate these and provide an opportunity for people to interact with them. On the Mantis stand were four “employees” who engaged delegates in conversation over the two days, surreptitiously noting responses and questions – handing out and collecting business cards from those who wanted further follow-up. On the second day of conference, we hosted a one-hour workshop titled “the development organisation of the future” – and invited participants to come and have their assumptions challenged, but with little other information. Over 100 people turned up. In this session we “revealed” that Mantis did not yet exist and asked people to undertake some rapid group “sense-making” to uncover potential implications and opportunities for their own organisations.

The reactions

During our time on the Mantis exhibition stand, we spoke to around 80 people. Most were intrigued and excited by the alternative approaches taken by Mantis. Offers to speak at events, publish articles, and explore funding or partnership opportunities validated the Mantis concept. It also demonstrated to us an openness among a wide variety of sector professionals to embrace entirely new approaches. We found this hopeful, particularly given the common perception of the sector as sometimes being slow or resistant to ideas from outside.

“We are currently developing a pipeline of new programmes and we have nothing in our portfolio that speaks to the type of interventions and approaches that you have. Can we partner and you guys can help us out?” NGO employee

“We are working on a campaign for XXX. We want to work with Mantis to use its AI brain to develop multiple strategies and interventions across the region to address this issue.” NGO employee

A few visitors to the stand raised thorny questions about the ethics of Mantis operations:

“I see that your project is extremely ambitious. However, it also raises inevitable and profound ethical and regulatory concerns. How long will you be able to look after each Mantis action and decision, until you don’t even understand the predictions or actions it is making anymore?” Software developer

“Do you ask people if you can use their data? What are people told when they download the app or use the game? Do you sell or share the behavioural insight data with anyone else? Beyond this, what open source data is Mantis accessing? How do you verify that this data is actually open source? How do you ensure the data or those people in crisis situations is kept safe and secure?” Campaigning organisation

Others saw the immediate threat to their organisation:

“The way you engage citizens to work for you completely makes our company redundant. We should talk.” Private sector company

Most, however, of the hundred plus delegates who attended the “reveal” workshop on the second day of Bond conference hadn’t visited the Mantis stand. After a short presentation about Mantis, we asked delegates to reflect on three questions: What makes you uncomfortable? What areas of potential can you see? What are the first steps for you to explore potential opportunities for your organisation?

In response to the first question, people voiced scepticism about the ability of simulations to accurately reflect reality. There was lots of debate about how to ensure unbiased data and access to technology for the most marginalised, as well who would be accountable when Mantis “went wrong”. Concerns were raised about the effects of automation on people’s jobs, the ethics of providing a monetary incentive, and the loss of human interaction.

Areas of potential identified were more meaningful ways of engaging citizens, as well as engendering cooperation between people to solve problems. The ability to use data in new ways – from citizen-driven data advocacy to improving the effectiveness of decisions was clear. The potential to ‘learn lessons’ through AI simulations without “real risks” also emerged in one group.

As an immediate next step, almost all groups identified the need to explore how to use existing technologies better, and gain confidence and knowledge in emerging technologies such as AI. Tech horizon-scanning, the responsible use of data, and creating more spaces for innovation were also highlighted.

The broader implications

“The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.” William Gibson.

For some people the technology behind Mantis might have felt far-fetched, but many of the key components of Mantis were extrapolated from weak signals. In other words, while Mantis as an entity doesn’t yet exist in the development industry, many aspects of the way Mantis operates are already real, or becoming real.

For example, a powerful AI, capable of anticipating the implications of alternative courses of action is central to Mantis. Whilst this may seem like science fiction, Deepmind is already developing an AI with “imagination” – enabling machines to see the consequences of their actions before they make them. The Mantis AI’s use of citizen-generated situational data to predict changes in local environments is foreshadowed by existing organisations, such as Premise. While initiatives such as the UN Global Pulse Lab’s Vampire project in Indonesia is already analysing multiple big data sets to provide “vulnerability mapping” and a real-time early warning system for climate impact. Distributed, virtual organisational structures like Mantis already exist too – Colony.io, for example, is building the infrastructure for “self-organising companies that run via software rather than paperwork”. Meanwhile, having a machine as your manager may not be far off either, if the early experiments of automating management functions and task allocation such as iCEO and Flash Teams are anything to go by.

We hope development professionals take from this the importance of looking to the “margins” – and not just of their own industry – to spot those early signals that can help us understand how the future may be changing.

We also wanted Mantis to pose some tricky questions about the future of development organisations: their purpose, how they’re structured, the type of interventions they make, and how they’re funded. Here’s our “guide” on some of the ways we think Mantis differs from a generic “typical” development organisation. We didn’t set out to produce something diametrically opposed to many of our existing institutions, but it is interesting that this was the outcome. What might it look like for some of our established organisations to adopt one or more of these features?

Table 2: What’s different? Mantis vs typical development organisations

| Typical development organisations | Mantis | |

| Purpose | Provide basic standard of living and rights | Prevent future dangers to the global system (ecological and social) from materialising through strategic risk mitigation |

| Delivery | Project-itis and sector silos, narrow geographic focus | Systems-wide, global |

| Structure | Ossified centralised hierarchies | Small, virtual, nimble, distributed |

| Approach | Delivers pre-planned activities. Operates on basis that environment is predictable and outcomes are “known” | Thrives on uncertainty, constantly testing and reassessing. Prepared to do things that might be ethically dubious to achieve goals |

| Interventions | Reactive, problem-fixing | Preventative, anticipatory, adaptive |

| Technology | Marginal use: process innovations for existing activity or small-scale new product development | Central to organisation: provides analytical capability and decision-making; automation of management functions and tasks |

| Inputs to decision-making | “Small” data, government/donor agendas, beneficiary-identified needs | Big data, behavioural insights, simulations + scenarios |

| Funding | Public money (government funding or individual donations) | Insurance models; private sector risk mitigation payments |

| Staffing | Professionalised, permanent employees | Citizen volunteers, and gig economy workers |

What we wish we’d done differently

Inevitably, there are a few things we would probably do differently if we could turn back the clock.

- Created a range of future development organisations

Time and budget constraints aside, we would have loved to present other possible “future” development organisations in addition to Mantis. We think this would have really helped stretch perspectives into a range of alternative futures. - Held a longer “sense-making” session

By launching Mantis at Bond conference we were able to reach a large number of development professionals, but were constrained by the breakout session format of only one hour. With longer, we could have delved deeper and allowed greater space for reflection, which might have helped delegates uncover more immediately actionable steps. - Gathered more and better quantitative data

We made efforts to gather feedback in a way we could quantify – through a poll and rating system accessed via the Bond conference app, and through the end-of-day evaluation form for the conference. However, response through these mechanisms was just too low to have any meaningful statistical significance (2 responses via the app and 11 via the paper evaluation forms). Stronger signposting and incentives for completion might have increased this response rate. In an ideal world, we might also have surveyed for views on the future of development organisations before and after exposure to Mantis.

What we learnt

It’s still only a few weeks since we launched Mantis, so the chances are that we’ll pick up a few more “learnings” as responses and conversations percolate, but here are our current top three:

- The value of the foresight and speculative design process to generate less obvious insights

The process [see above] that we went through to create Mantis is far-removed from a typical corporate strategy or planning process that our own organisations, clients or members would normally go through. This helped put us in a position to uncover less obvious insights, be able to ask different questions and actually generate new ideas that stretched us beyond current thinking. - Shifting thinking is hard… but it happens when people actually experience the future in a tangible way

When presented with a powerpoint presentation of future trends our experience is that it changes little; people continue to think from a perspective of underestimating the costs of business as usual and overestimating the risk of doing new things. Faced with an organisation that appeared real, each person who came to the Mantis stand tried actively to engage with Mantis – either seeking out the opportunities or assessing the threats. We felt this helped skip over the “not relevant to me” response that we’ve seen before. - Thinking radically about the future doesn’t need to be left to outsiders

The conversations after the workshop and in the days since have left us with a real optimism that there are development professionals who want to create radically different futures for our institutions. Can we now harness this, and build a community of these change-makers?

“I see this as a shot across the bow…. We need to be thinking more nimbly.” NGO employee

Now what?

We’re all busy developing ideas about what we do next, so watch this space.

Over the next few months Bond will be hosting a range of opportunities for its members to learn more about emerging technologies and to consider the implications for their own work as well as society more broadly. If you’d like to find out more, please join Bond’s futures and innovation working group.

And if you didn’t catch Mantis at Bond conference, you’ll be able to meet us again at Nesta’s FutureFest in July (but shhhh, we’re counting on you to keep the secret to yourself!).

“If our assumptions and images of the future remain undeveloped, undisturbed and uninspired, then the ideas and conceptual prototypes that are produced reiterate business as usual and used futures.” Jose Ramos