Why the UK government and others need to balance ‘growth from above’ with ‘growth from below’ if it wants to reduce poverty in our crisis-ridden world

On the back of Covid-19, high inflation and the uncertainty of climate-related disasters and other crises, many governments – particularly in low-income countries – are reverting to old-fashioned growth strategies.

This often involves export-oriented growth and industrialisation with a primary focus of increasing GDP. In some cases, it involves supporting economic transformation through large, formal investments in infrastructure, health, education and public-private partnerships to enable workers to move from agriculture to non-agriculture (especially to manufacturing and services), and from less to more productive sectors.

A problem with these traditional ‘growth from above’ approaches is that often they don’t help people escape poverty. This is because most people in poverty are unable to access the higher productivity jobs these growth strategies aim to generate due to limited availability, skills or networks. Instead, most people in or near poverty increase their income through ‘growth from below’, which involves small investments by households in micro-enterprises, smallholder agriculture, the rural non-farm economy (such as manufacturing, handicrafts and retail trade) and the urban informal sector (such as informal construction work, transport, street vending and domestic work).

Growth from below

Supporting growth from below in our era of uncertainty requires governments or donors, including the UK’s Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), to implement measures that guard against various sources of risk, from climate-related disasters to ill health, which at best undermine pro-poor growth and at worst harm people in and near poverty.

Growth from below may still be inadequately recorded in national accounts. But it is generally agreed that it provides a substantial proportion of total economic growth, contributing significantly to GDP as well as employment.

At the Chronic Poverty Advisory Network (CPAN), based at the Institute of Development Studies, we argue that the FCDO, along with other donors and governments, need to balance support for growth from above and growth from below. This needs to be done through context-specific approaches, alongside collective risk mitigation, to make economic growth a more effective mechanism for reducing poverty amid the uncertainty of climate change and other crises.

Supporting inclusive growth in mineral economies

Our work in mineral economies in Zambia and Nigeria shows that careful macro-economic management is needed if the economic growth which these critical minerals bring is to benefit those on very low incomes. Without careful management, there is a risk of boom-bust mineral cycles, overvalued currencies which discourage non-mineral exports and agriculture, and reactive policy responses that may end up harming people in and near poverty.

Sign up for Network News

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Subscribe bowFor example, in Nigeria, the Central Bank’s cashless policy, fuel subsidy removal and exchange rate reform is driving up poverty in the absence of adequate mitigating measures to unabated cost-of-living increases, including transport price rises.

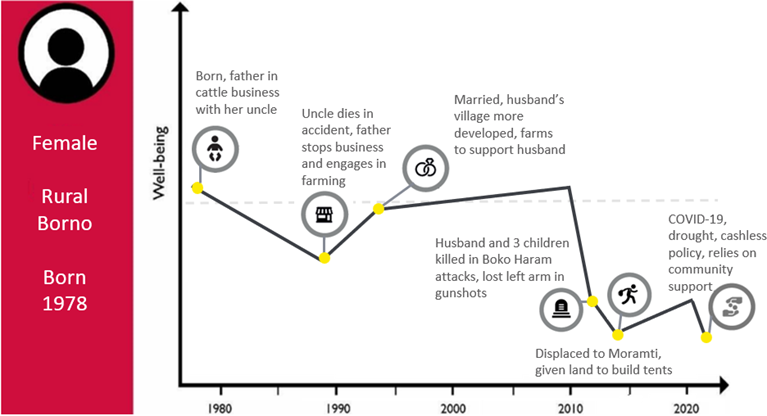

The illustration below of a woman’s life from Borno, Nigeria, based on an interview with CPAN, illustrates how poverty has been made worse by government policies and economic crises in recent years despite violent conflict subsiding.

Mining companies are powerful stakeholders and drivers of growth in economies like Nigeria and Zambia. Governments could develop regulation or contracts with these companies to reduce poverty in and near growth hubs. This can be done through corporate social responsibility or other mechanisms designed to support local benefits, require local content in supply chains and enable inclusive growth.

There is also a need for strategies to prevent conflict from widening inequalities, including conflict caused by mining operations. This can be done by promoting peacebuilding and developing or reinforcing anti-discrimination measures or progressive taxation to curb inequality. Given that conflict has a negative impact on economic growth and can also push people into poverty, conflict prevention can play an important role in creating enabling conditions for inclusive growth.

Because of the high level of inequality in mineral-based economies, government interventions need to support poverty reduction, which requires dynamic taxation and context-appropriate public spending on areas such as health and education, as well as enabling growth from below.

Strategies for inclusive growth in farming-based and industrialising economies

In largely agricultural economies, such as Malawi, Tanzania and Rwanda, to encourage inclusive growth there is a need to continue supporting the diversification of smallholder farming households, micro, small and medium-sized enterprises and links between formal and informal services. Supportive policies, such as insurance for livestock, crops and credit, are also needed, not least due to the increasing frequency of climate-related disasters. Social assistance can play an important role in bringing the poorest people nearer to the right side of the poverty line. Combined with other small/micro business and agricultural policies which make markets work for the poor, this can lay a foundation for escaping poverty.

In industrialising economies, such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, Kenya and Ethiopia, to achieve growth that also helps reduce poverty, it is important to strengthen links between formal and informal firms, and gradually extend health and safety and minimum-wage conditions into the informal economy, including a focus on closing gender wage gaps. This can provide an important pathway out of poverty and drive growth, including through remittances.

The equitable treatment of migrant workers, who make up a large proportion of the informal workforce, is key to supporting these pathways. This, in part, requires enforcing labour laws, improving working conditions (and collective bargaining that can advocate for this) and ensuring undisrupted access to services. Supporting informal workers can also help address challenges commonly associated with unmanaged urban expansion that may accompany growth which can deepen spatial inequalities and constrain environmental sustainability. Alongside this, prioritising infrastructure development and service provision in low-income settlements is long overdue.

Policies to shape inclusive growth

There are also general policies and programmes to consider to shape inclusive growth. These include: supporting smallholder, climate-smart agriculture and food security, supporting the urban informal sector, not just the top firms, to improve productivity, inclusion and environmental sustainability, and supporting human development (health, education, social protection), including skills development.

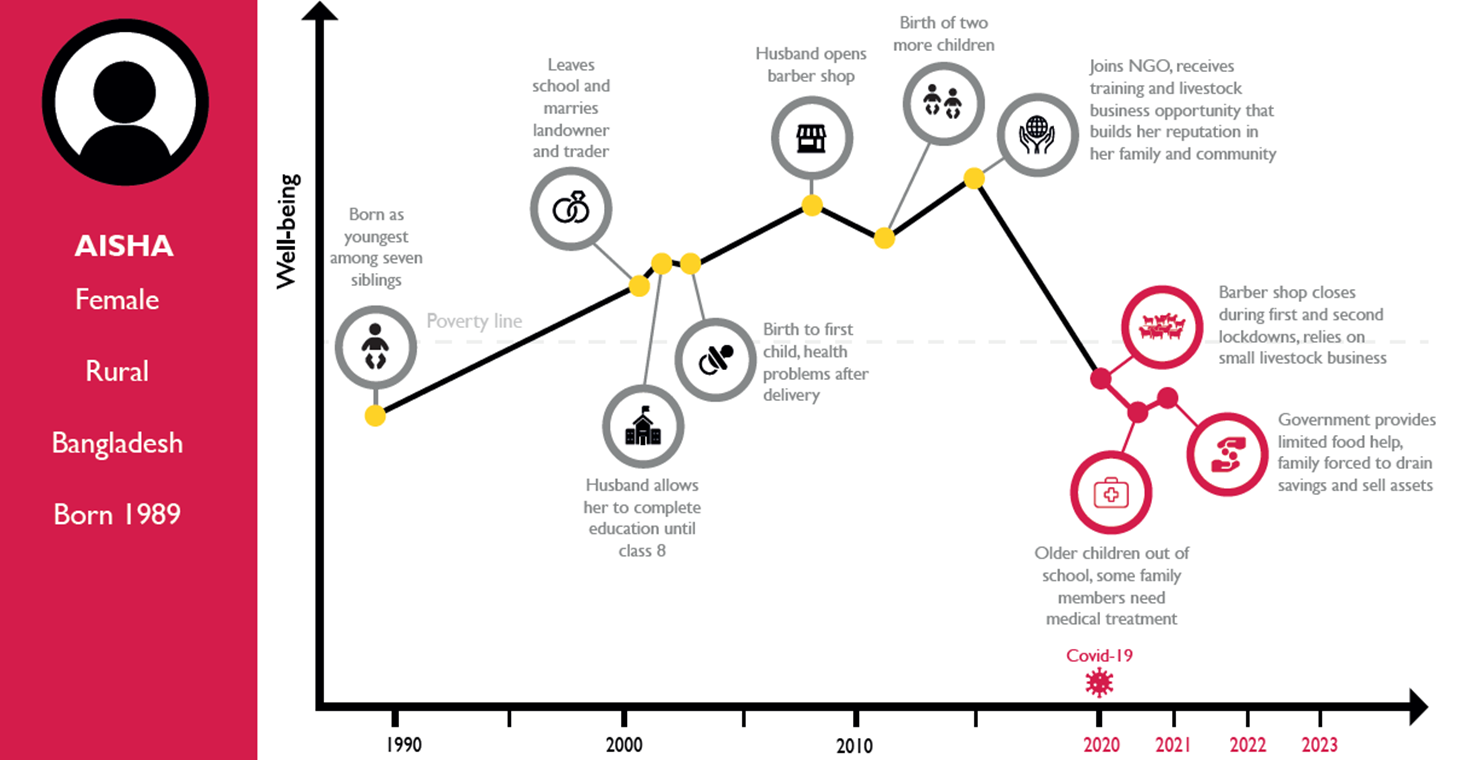

In all of this, guarding against economic, environmental and health risks needs to be a critical part of the agenda. These risks so often drive impoverishment, which counteracts the gains from growth and human development. For example, as this graphic below shows, while off-farm diversification enabled Aisha and her husband to escape from poverty in Bangladesh at the turn of the 21st century, government support was unable to prevent them from sliding back into poverty during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Depending on the context, managing these risks may require concerted peacebuilding, insurance mechanisms or strengthening disaster risk management capacities, including the often neglected arm of post-crisis recovery.

Overall, governments of low-income countries, and the FCDO and other donors, need to implement inclusive growth policies to support the type of growth that also helps reduce poverty. Policies are needed that promote elite interests in poverty reduction, whether by placing poverty reduction at the centre of policies for economic growth or linking growth strategies to international commitments.

Drawing on coalitions of support – comprising of the FCDO, low-income country governments and other donors working with NGOs, CSOs, the private sector and other key stakeholders – before, during and after crises can also go some way towards enabling more equitable growth strategies in our era of uncertainty.

Category

News & Views