More cuts to the UK aid budget under the new government’s first Autumn Budget

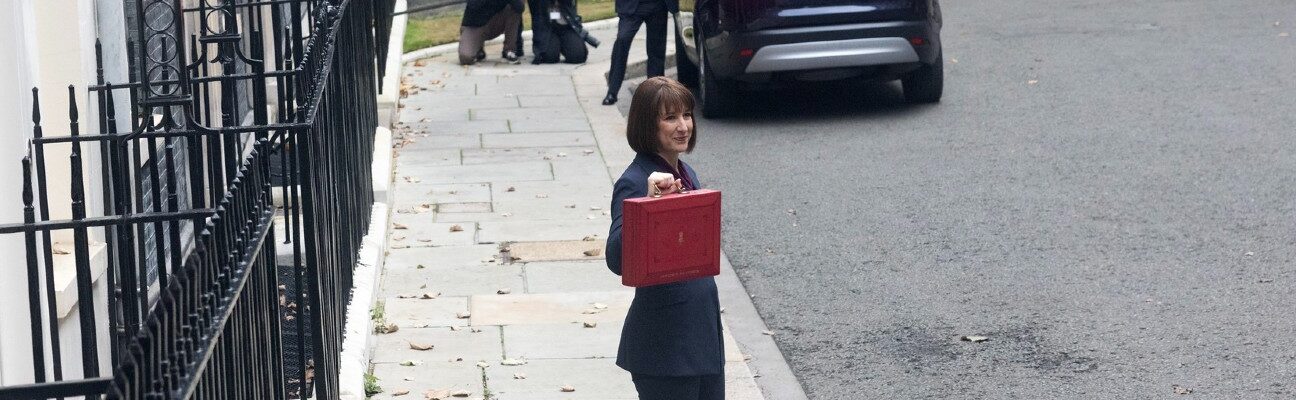

Yesterday the government announced its Autumn Budget – Labour’s first budget for 14 years.

It has been in the headlines for weeks now, and whilst the domestic implications will gain most attention, this Budget also gives us crucial insights into the new government’s approach to and funding for international development.

What is our verdict?

This is a deeply disappointing budget for the development sector. After having repeatedly promised to rebuild trust in the UK as a reliable development partner, the government has introduced new cuts to the UK aid programme and pushed off returning the UK aid budget to 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) indefinitely.

The budget confirmed the following:

- UK aid will drop sharply from £15.3bn (0.58% of GNI) in 2023 to £13.7bn (0.5% of GNI) in 2024, with a slight increase to £14.3bn in 2025 (0.5% of GNI). Departmental ODA allocations given in the Autumn Budget will be at £13.3bn for 2024/25 and £13.7bn in 2025/26.

- A commitment to bring asylum costs down, including by ending expensive hotel accommodation, but no tangible commitment to reforming the current approach of using UK aid to cover the costs.

- The government will apply the same unrealistic and discredited fiscal tests for returning the aid budget to 0.7% of GNI as the previous government and stated that these tests will not be met in this parliament.

No additional ODA or reporting reforms to manage the pressures of supporting refugees in the UK

In September, over 120 NGOs called on the government to prevent further cuts to the UK aid budget by providing additional resources beyond the current 0.5% of GNI aid target, reducing the amount of UK aid being spent within the UK on refugees and asylum seekers, while still ensuring adequate support for this vulnerable group, and setting out new fairer plans for how and when the government will return to 0.7%. The Autumn Budget did none of these things.

In the 2022 Autumn budget, the last government provided an additional £2.5 billion in ODA above 0.5% over two years to help manage the pressures of high levels of ODA spending in the UK to support refugees. Despite comparable pressures now, the government has failed to add any resources to the ODA budget above 0.5%. As a result, the ODA budget will fall dramatically in 2024/25 and FCDO will need to make significant cuts to its programmes.

The government has also confirmed to Bond that it is not considering reforms to its methodology for reporting ‘in donor refugee costs’ as ODA, despite the fact it has been criticised by the OECD for failing to comply with its rules to report these costs ‘conservatively’ (in fact the UK reports higher costs per refugee than any donor).

The failure to supplement the ODA budget to reflect these spending pressures is all the more disappointing because the Treasury identified asylum cost pressures as a major element (£5.6bn) of the £22bn ‘black hole’ identified in its ’public spending audit 2024-25’. Yet the Treasury was not willing to use any of the finances raised to fill this hole to provide additional resources to UK aid, the budget that is bearing the brunt of uncontrolled asylum spending.

Additional pressures on next year’s budget

Though ODA is planned to grow slightly in 2025/26, it will remain at 0.5% of GNI, significantly below its 2023 level of 0.58%. Whilst this increase is welcome, it will be insufficient to adequately address the growing pressures on the ODA budget waiting in the next year.

Save the Children have calculated that FCDO cuts this year have been achieved largely due to “deferring promised funding into future years”. While most of the FCDO’s budget for 2025/26 seems already allocated, it is also dominated by (mostly deferred) multilateral pledges such as the disbursement of £707 million to the World Bank IDA planned for this year, which would have been sufficient to support World Bank IDA to provide essential health, nutrition and population services to nearly 14 million people and more.

Crucially, the next financial year is also the last year of the UK’s commitment to spend £11.6bn on climate finance by 2026, with £3.4bn required to be delivered in 2025/26 alone, an increase of £0.9 billion on 2024/25, significantly above the planned increase in ODA. The government is yet to commit to honouring this pledge, but if they were to in the context of no additional ODA above 0.5%, this would place enormous pressure on wider development spending.

Finally, over the next two years, the UK will be required to make new pledges for funding World IDA, GAVI, climate finance (at COP-29) and biodiversity finance (COP-17), amongst others.

Fiscal rules push off a return to 0.7% indefinitely

We have urged the government to introduce fair and transparent fiscal tests for returning the ODA budget to 0.7% of gross national income (GNI), and to scale-up ODA as progress is made towards meeting them.

The prevailing fiscal rules have only been met once in the last 20 years (the Chair of the IDC, Sarah Champion, called them “an almost impossible test”), and as the government has changed its own fiscal rules they are now less likely to be met and less coherent with these new rules (see this blog by Save the Children).

Despite this, the government has decided to continue with the existing fiscal rules for returning to 0.7%, which has seemingly pushed off this decision indefinitely.

Another opportunity ahead

The Autumn Budget was a missed opportunity by the new government to rebuild trust in the UK as a reliable development partner, and the resulting aid cuts and heightened spending pressures will harm those facing poverty, humanitarian crises and climate change.

The multi-year Spending Review, launched by the Chancellor to set spending plans for at least three years, is supposed to “bring spending back under control.” This is yet another opportunity for the government and as part of the review the government needs to

- Begin increasing UK ODA back towards 0.7% and set a clear timetable for achieving it

- Reform the methodology the government has inherited for reporting ODA spending on refugees to make it more ‘conservative’, and, over the long-term, fund vital support for refugees from other budgets outside of ODA.

Without these steps the UK cannot be said to be ‘back on the global stage’, as it claims. We look forward to engaging with the government around the Spending Review to pursue this agenda.

Category

News & views