Shifting power to save lives: how the new UK government can become a champion for global partnerships and local leadership in crisis response

The change in government in the UK with David Lammy as Foreign Secretary and Anneliese Dodds as Minister for International Development offers an exciting opportunity to change the way that the FCDO does aid and diplomacy to shift power to national and local organisations at the frontlines of crisis response.

Lammy talks of wanting to forge a new approach to global partnerships, leveraging what the UK has to contribute, but also respecting and making the most of the expertise and influence of others around the world. What might a new approach to partnerships and local leadership mean for the government’s approach to humanitarian action?

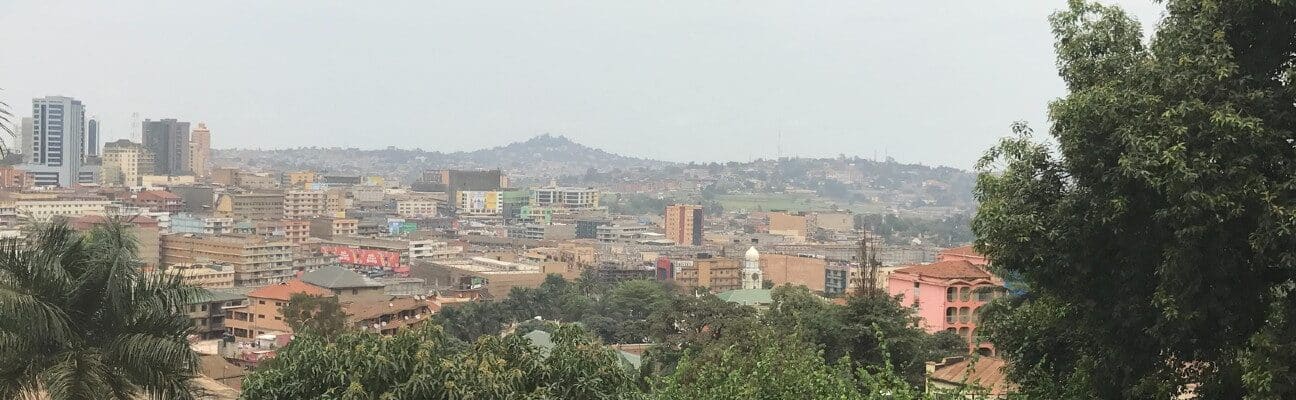

We work for CEFORD, a Ugandan national NGO that also acts as secretariat for the Charter4Change coalition, campaigning for locally-led humanitarian action, and CAFOD, a UK-based international NGO that has a long history of solidarity and partnership with local civil society groups around the world.

Exactly one year ago, we supported FCDO in an unprecedented FCDO dialogue with local civil society in Ukraine, Myanmar and South Sudan to identify how the UK can better support locally led humanitarian action. Unlike most donor policy debates on ‘localisation’, the FCDO Dialogue took steps to join up the dots in discussion between FCDO headquarters decision-makers with UK embassies and local civil society groups, and their networks, at the country level.

It included diverse groups from Ukraine, Myanmar and North West Syria, including those representing LGBT, faith, persons with disability and women’s rights movements. A survey of local actors was conducted by the Overseas Development Institute and FCDO issued a report with recommendations emerging from the Dialogue earlier this year.

Since then, officials have started scoping a whole-of-FCDO (not just humanitarian) localisation strategy, but the election inevitably led to a pause and now an opportunity to reflect.

What next?

Based on the above efforts to listen to local civil society groups and dialogue with FCDO officials, we highlight the following four recommendations:

Hold international agencies accountable for equitable partnerships and support to local leadership – One very practical action that FCDO could take would be establishing a global, consistent approach to fair overheads cost support for local organisations, and holding international agencies accountable for providing this to them. Concerns about risk management, quality and accountability are often cited as obstacles to ‘localisation’, and yet the current approach too often involves not covering local NGOs’ running costs, undermining their organisational capacity to effectively manage the risks they face. FCDO developed good guidance on overheads for its Rapid Response Fund, but since then has not mobilised that mechanism. That policy should be adapted and rolled-out across all FCDO funding. A deeper shift on equitable partnership would be to make this an explicit priority in all grants and consortia involving work with local groups, and to establish systematic mutual accountability stock-takes in which local groups’ feedback on partnership quality get heard and acted on.

Scale-up locally led funds at the country level which demonstrate a genuinely transformative approach, and appoint the right staff to manage these – The FCDO Dialogue in September 2023 revealed that the UK is already supporting some country-level funds and consortia innovating in support to local groups. A contextualised approach is essential to understanding risks facing local groups and finding practical ways to mitigate them. But these are few and far between, and reliant on individuals – they have happened where there are supportive senior embassy officials and fund managers in place. So the FCDO needs to hire staff with that expertise and commitment to shifting power to local groups and ministers need to give their political backing by making the case to Parliament and the media for solidarity with local first responders in times of crises.

Use the UK’s influence with humanitarian coordination agencies to ensure meaningful participation by local actors in decision-making – UN coordination processes tend to emphasise the numbers of local groups that “participate”, but if that participation doesn’t involve meaningful influence on decision-making, nor result in plans that better support local groups, this isn’t good enough. UN-led Humanitarian Country Teams in a number of contexts have been developing ‘Localisation Strategies’, but these are yet to see real momentum or accountability behind them. This needs to change. Area-based coordination offers potential for more inclusive, collaborative decision-making at sub-national level. And the UK should fund local actors’ own networks and their own coordination, and ask international agencies how they’re supporting that.

Set targets for increasing direct and indirect quality funding to local organisations – In 2022, FCDO data suggests that UK humanitarian funding to local actors stood at just 6%, or only 2.4% if UN pooled funds aren’t included – far from the global target of at least 25% to national/local actors. The next financial year for FCDO offers an opportunity to set global and country-level targets to increase direct and indirect funding (including multi-year, flexible funds) to national NGOs. Under Samantha Power’s leadership, USAID adopted ambitious targets to increase direct funding to local actors, and this has helped to drive change. Whereas much of USAID’s localised funding goes to bigger national NGOs that resemble INGOs, FCDO could focus on support to more diverse local groups which often have access where others do not, such as local faith groups, women’s groups and others. Adopting proportionate, tiered approaches to the administrative expectations of grant applications and reporting will be key to enabling access for smaller, local groups. Between now and next Spring, Embassies could consult on what is feasible and strategic, as well as gather wider input to shaping FCDO’s global ‘localisation’ strategy.

Lammy and Dodds need to be mindful that lots of INGOs and UN agencies are seeking to rebrand themselves as localisation allies, but few are making substantive changes. FCDO should challenge their partners to do more and better. Is an INGOs’ ‘capacity strengthening’ work genuinely leading to enhanced local leadership in programming and access to funding, or is it keeping local NGOs dependent on the INGO? Or is a so-called ‘localisation funding platform’ really empowering local groups, or is it just a rebrand of old-school, top-down sub-granting to them?

The good news is that there are pockets of innovative practice in what FCDO supports, such as in Afghanistan and Bangladesh. Back in 2004, a previous Labour Government championed reform of the UN humanitarian system, getting the UN to establish pooled funds and cluster coordination to address the chaos of uncoordinated, poorly prioritised humanitarian response.

Almost a decade later, this new Government has an opportunity to help catalyse equally radical, transformative shifts by getting both UK-based INGOs, the UN and others to recentre crisis response on local community groups and networks. The fact is that local groups are already the first to respond, and international agencies already often rely on them. The UK should have their back.

Category

News & views