Mental health and psychosocial support: Seven elements for effective programmes in peacebuilding

Peacebuilders are increasingly recognising the central role of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in breaking cycles of violent conflict.

Poor mental health can undermine social cohesion, fuel mistrust and anxiety, and hinder efforts to resolve conflicts non-violently.

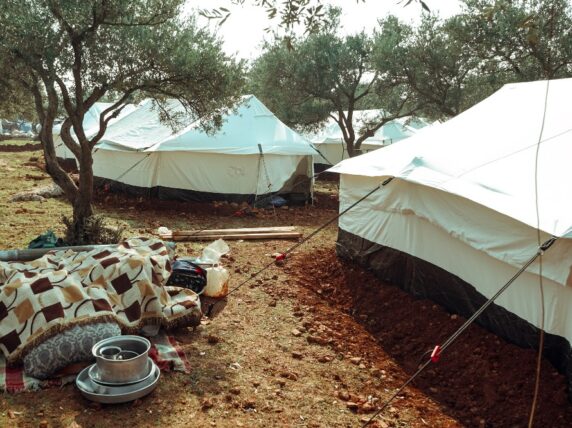

At International Alert, we’ve been integrating mental health and psychosocial support into a number of our country programmes for some time. We knew that it helped, but we wanted to better understand why. Our recent research, Peace of Mind, took a closer look at two of these programmes, in Rwanda and Tajikistan, to assess the effectiveness of our approach two different contexts, and explore the ingredients that contributed to positive outcomes we observed.

Mental health work, particularly when related to trauma and in conflict-affected settings, comes with risks. Delivered in isolation, well-meaning programmes can unintentionally trigger distress, cause social stigma, or contribute to conflicts. We wanted to identify those aspects of the projects that ensured mental health interventions were contributing to peace.

We identified seven elements common to both projects that enabled effective integration of MHPSS in peacebuilding programmes:

1. MHPSS that is context specific and culturally sensitive

Many people find that stigma is a major barrier to getting mental health support, and the way that communities talk about trauma and healing can vary dramatically. Psychosocial services, whether individual treatment or community-based therapy groups, should be grounded in local understandings of mental health and should make provisions for people with specific vulnerabilities.

“I did not want to participate at first due to my shame,” one female project participant from Tajikistan shared. “But, after taking part in the project, my outlook changed. I began to speak to different people in the village… I now feel like I am part of the community again.”

2. Increased economic opportunities

Community and individual wellbeing are closely linked to financial security. In Tajikistan, income generation activities were found to improve mental health and transform attitudes towards women, a longstanding driver of conflict.

Positive economic interactions can also create opportunities for partnership and collaboration. Almost all respondents (99.5%) in Rwanda saw reconciliation in this way. Integrated MHPSS and income generating activities can help empower previously excluded people, bridge divides between social groups and create more stable communities.

3. Safe spaces for positive interaction

“I was afraid of meeting genocide survivors against whom I committed crimes,” said Bernard, a project participant from Rwanda, who credits community dialogue groups (Duhuze forums) with helping him overcome his fear and open up. “We met at our local meeting hall and had an open conversation on the wrongs that we did to them.”

Sustaining and supporting places to bring people together improves trust, community ties, and group solidarity. Conflict-affected communities often lack spaces safe enough to discuss sensitive subjects. Creating an inclusive and accepting environment can help to work across generational, gender-based, or other social divides. Such spaces offer opportunities to address past wounds, while managing the challenges of today and encourage hope in the future.

4. Education for communities on mental health

Ongoing discussion and reflection can help address stereotypes, misunderstandings, stigma, and other barriers for people seeking support. Creating more accepting environments, particularly in societies affected by violent conflict, is a process that needs to be continually strengthened.

In Tajikistan, for example, our projects encouraged family members to explore the harmful patriarchal norms that affected wellbeing, seeking to shift attitudes and allow women to realise their potential. By normalising discussions about mental health, peacebuilders can support open environments for those needing help.

5. Redress for past violence, such as legal assistance for survivors

In Rwanda, large numbers of people saw apology, justice and legal processes as key parts of reconciliation, while in Tajikistan, free legal services have helped support women to defend their rights. “I was able to learn a lot about what rights I have or do not have as a wife,” said one Tajik participant. “If we get legal and psychosocial services [together] it will really benefit [local women].”

Individual and community healing is often held back by frustrations at incomplete justice, and effective MHPSS goes hand in hand with context-appropriate legal assistance, such as partnerships with justice organisations or referral services.

6. Peaceful resolution of disputes and non-violent communication

Non-violent communication and conflict management are skills that require time and investment to improve. Findings from Tajikistan showed how difficulties in talking can openly lead to domestic conflict, with men regularly blaming women for being unable to provide for their families. “Violence happens when there is no mutual understanding,” as one young male participant put it.

To enhance social cohesion and reconciliation, MHPSS needs to be accompanied by peaceful dispute resolution, conflict management, mediation, and non-violent communication. Local service providers and local leaders can play a key role in addressing tensions when provided with technical support, training and resources.

7. Negative gender norms that increase psychological distress need to be addressed

We found that negative gender norms considerably increased psychological distress, while also presenting a major barrier to access. In patriarchal communities, women often report worse mental health outcomes, yet are cut off from seeking support. Sensitisation around gendered stereotypes and vulnerabilities can help tailor services to the needs of their participants, improving effectiveness.

Underpinning each of these elements is the fundamental truth that runs through all peacebuilding interventions: that locally owned and led activity will be the most effective and sustainable. As always, those best placed to address conflict are those directly affected by it. Done right, integrated mental health support can demonstrably lead to stronger, more inclusive and peaceful communities, resulting in people feeling more positive and hopeful for the future.