Racism in the humanitarian sector endangers aid workers’ lives

In this blog, we recognise that the concepts of “race” (including the terms “white”, “Black”, “brown”), “ethnicity”, “nationality”, and many others are socially constructed. Because the term “race” is controversial in some languages and many are unaware that the term does not reflect any biological reality, we decided to emphasise the artificial nature of this concept. In this blog and in the paper, therefore, the term “race” will be shown within quotation marks.

The Black Lives Matter movement has highlighted the extent to which the aid sector is also affected by racism, sparking important conversations around how racism within organisations can affect an aid worker’s career and wellbeing.

However, until now, the physical security implications that “race” and racism can have on aid workers have rarely been discussed.

Aiming to start this conversation, the Global Interagency Security Forum (GISF) recently published research by Tara Arthur and Léa Moutard. They interviewed 20 aid workers from across the sector about their experiences regarding “race”, racism, and nationality. The findings showed that racism within organisations could endanger aid workers’ lives.

Racism endangers aid workers’ lives

In this research piece, some aid workers shared that they were deployed to contexts where it was assumed they would “fit in” more easily as aid workers of colour. In other instances, aid workers felt that their profile and specifically their nationality and/or “race” were used as a strategy to minimise risk for their organisation without sufficiently including measures to keep them safe.

Security plans often did not include measures that would take into consideration the profiles of those from non-white backgrounds. Others mentioned that conscious and unconscious biases appeared to influence whether their security concerns were even heard when they voiced them to their teams and managers.

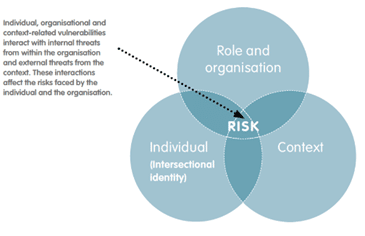

Employing an inclusive person-centred approach to security risk management means identifying the specific risks aid workers face by looking at how their personal characteristics, including their nationality or “race”, intersect with the context they work in and the organisation they work for. This approach is key to understanding the unique security and safety threats an individual may face. Ignoring this dynamic and failing to address the risks specific to staff from different backgrounds means that risks for these aid workers will not be identified, and thereby not mitigated.

Even more, ignoring the concerns that aid workers raise not only means that organisations might fail to meet their duty of care to take all reasonable measures to mitigate risks for their staff, but also reinforces feelings among staff that there is inequitable treatment. This was reinforced in the article by the fact that more than half of the interviewees felt as though there is an implicit hierarchy of humanitarian staff, including the prioritising the security of international aid workers over national aid workers, and prioritising white staff over staff of colour.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsHere are seven steps non-security staff should take to facilitate organisational and cultural change to address the security implications of racism

- Promote conversations on diversity and security: encourage open and genuine conversations in your organisation about diversity and security, including discussions about racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination. These efforts can also include conducting surveys or audits on inclusivity and diversity among staff.

- Provide training for staff on power and privilege: training on issues such as power, privilege, anti-racism, inclusion and biases should be provided to aid workers, including security managers and leadership. Such training is essential to ensure staff understand the various impacts of racism to enable them to apply an intersectional lens to all their policies, plans and activities.

- Address racism among aid workers: mitigating the security risks stemming from racism requires organisations to adequately prevent racist incidents and sufficiently address any that occur. Developing intersectional cultural security briefings, putting in place clear sanctions against racism in the workplace and protecting those speaking up against it are key to tackling racism and the security risks it generates.

- Ensure security risk management frameworks are developed collaboratively: individuals reflecting the full diversity of the staff covered by security risk management policies and plans should always be included in the development of frameworks at the global and national levels. This ensures that diverse perspectives are reflected and addressed holistically.

- Diversify security leadership: increasing diversity among security managers, especially at the global level, is a key component to understanding aid workers’ experiences and the impacts of security threats. To promote diversity, organisations should provide training, mentoring and networking opportunities for under-represented staff profiles, particularly people of colour, women, LGBTQI+ staff, etc. They should also create advisory groups on security that include staff from under-represented profiles who can bring in more diverse perspectives.

- Invest in lasting cultural change: leadership should demonstrate a real commitment to inclusivity and diversity. They must work effectively to address all forms of discrimination, including racism, sexism and ableism in the workplace. This means leading by example and making the necessary investments that can lead to deep positive change within organisations, including for security risk management.

- Support research on “race”, ethnicity, nationality and security: more research is needed to adequately understand how these issues impact aid workers’ security. Understanding the experiences of aid workers of colour, national and international staff, and the impact of ethnicity would help organisations develop adequate security measures.

To learn more about steps that you and your organisation can take toward inclusive security risk management practices, read the article here. If you want to join GISF in continuing this conversation, please reach out to Tara Arthur at [email protected] or Chiara Jancke at [email protected].

Category

News & ViewsThemes

Anti-racism