Global aid increased in 2020, but support for the poorest countries is waning

The Covid-19 pandemic has sparked the worst global crisis in generations.

Addressing the effects of that crisis and ensuring equitable access to vaccines, will be fundamental to ensuring the pandemic does not further exacerbate inequalities and lead to a lost decade on poverty reduction, rather than the decade of action promised at the beginning of 2020. Aid has a critical part to play in this, particularly for the poorest countries.

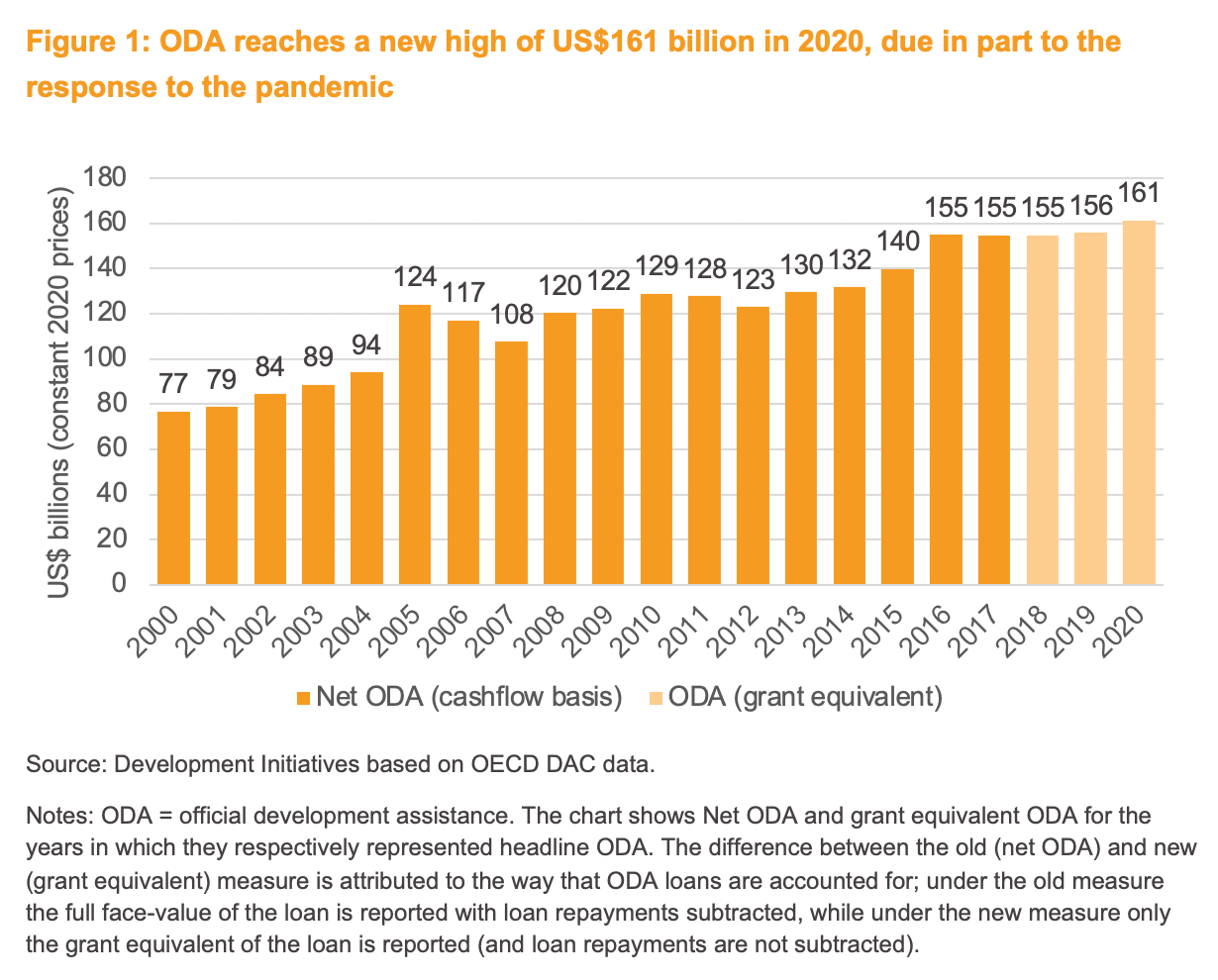

The latest global aid data released by the OECD last week shows that aid is up to an all-time high, as many donors increased their aid in response to the crisis in 2020. That increase of 3.5% represents US$5 billion in additional official development assistance (ODA), the first significant increase since 2016.

It is also vital that all donors ensure that aid is spent where the need is greatest. However, we see some concerning trends below the headline figures.

ODA is up, but many donors are still making cuts.

The increase in ODA reported last year is important. Despite fears of declining multilateralism, this is an important ray of hope. It demonstrates clear commitment from many donors that external support and resourcing is a priority for addressing the effects of the pandemic.

Despite significant economic challenges at home for all donors, many smaller donors reported increases alongside significant volume increases from Germany (increase of US$3.4 billion), the US (increase of US$ 1.6 billion), France (US$1.4 billion) and Sweden (US$927 million).

But this has to be seen in context of the cuts reported by just under half of DAC donors, which suggest that this commitment is not universal. The UK is the most significant of these, as one of the world’s largest donors and, at least until very recently, a global leader in development. The UK is set to lead several key global moments this year including the G7 Summit in June and COP26 at the end of the year.

The UK cutting its aid by US$2.1 billion compared to 2019 (in line with falling GNI) is a hit to global ODA levels. While the UK remained in the 0.7% club in 2020, the UK government will be stepping away from this commitment in 2021, as aid is set to be cut precipitously to 0.5% ODA/GNI with cuts announced yesterday. This decision seems at odds with the approach you might expect ahead of these key global moments.

These cuts are at odds with many other major donors: Germany re-joined the 0.7% group in 2020 with an increase in ODA/GNI level of 0.61% in 2019 to 0.73% in 2020 with Norway, Sweden and Denmark also increasing their shares in 2020.

Without better targeting of ODA to where need is greatest, we risk leaving the poorest countries further behind.

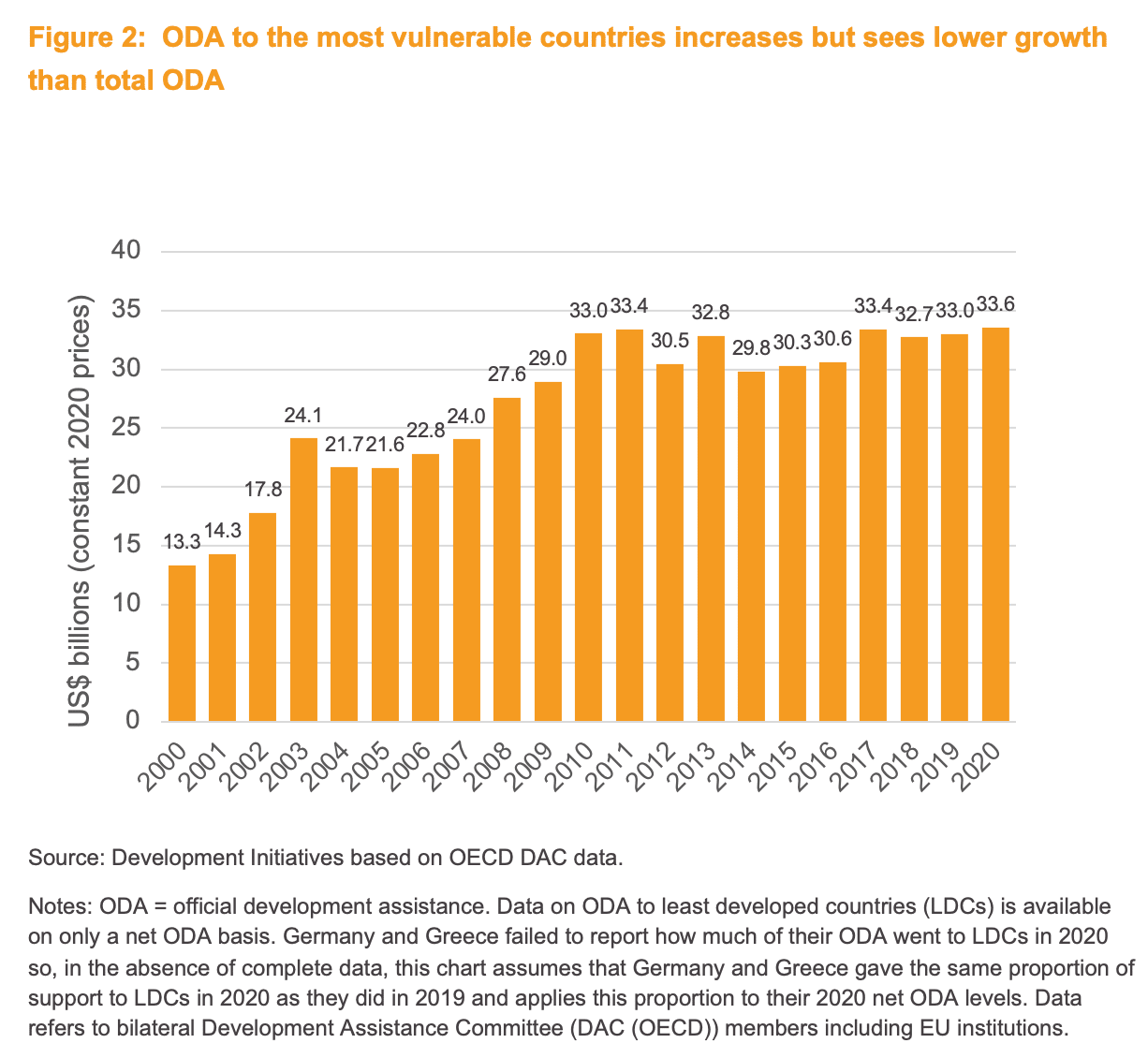

Least developed countries (LDCs) are facing serious challenges, which have worsened since the pandemic. While LDCs are home to only 15% of the global population, they are also home to 25% of the people pushed into extreme poverty last year, and 55% of those pushed below the $1 a day line.

They face severe and interconnected barriers to progress, not least of which are declining domestic resources and external financing flows, which have taken a hit in the pandemic. ODA remains a critical resource for many of these countries, representing the largest source of external financing, yet support to LDCs increased by only 1.8% (US$557 million) to reach US$33.6 billion.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsIt is worth noting that the picture is extremely varied when looking at individual donors. Some have posted much greater increases, notably Japan (by 29% from US$3.6 billion to US$4.6 billion), the EU Institutions (by 18% from US$4.1 billion to US$4.9 billion), and France (by 28% from US$1.5 billion to US$2 billion). But this was counterweighted by cuts from some donors. The UK alone cut more than US$750 million in aid to LDCs, a 20% reduction precisely as need and demand is growing.

A failure to reverse this trend and ensure that LDCs are more effectively targeted with ODA, risks leaving many countries behind.

And continued increases in lending deepens concerns of a debt crisis particularly for the poorest countries.

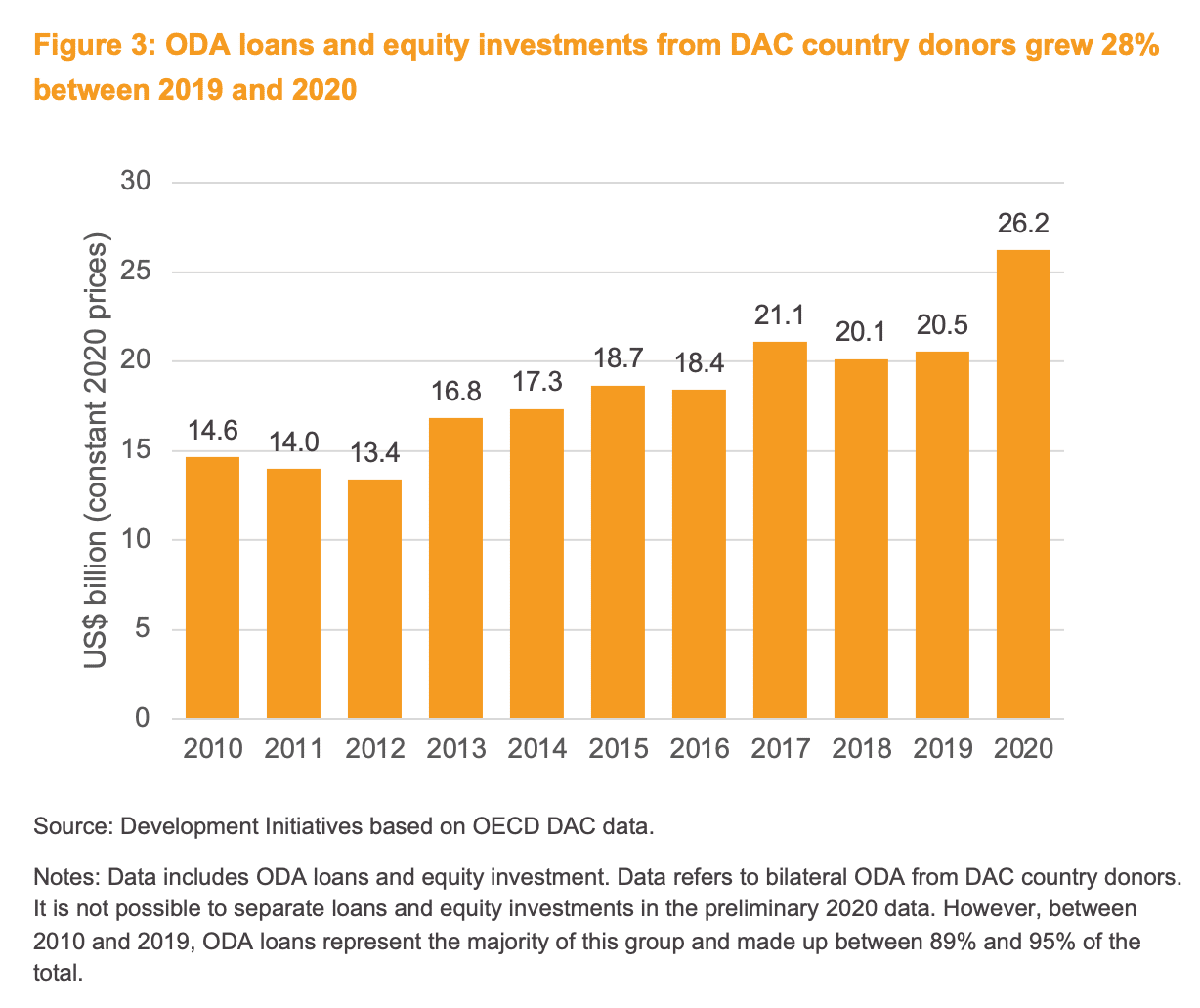

Beyond the more optimistic aggregate figures, there is also an increase in the use of loans and equity as a means to disburse ODA. This potentially poses challenges, with many countries already struggling with debt even before the crisis. While the current debt standstill arrangements have provided much needed breathing room, concerns remain that we are on the brink of another serious debt crisis.

Bilateral aid in the form of loans and equity investments is up by 28% in 2020 (reaching US$26.2 billion), a significant leap following a general increase over the last decade. They now make up almost a quarter of all bilateral aid (22%). Key donors that have driven this increase include France (an increase of US$2.6 billion or +55%), Germany (an increase of US$970 million or +21%) and Japan (an increase of US$1.7 billion or +18%).

While we do not yet know what proportion of ODA loans have gone to LDCs in 2020, we do know that between 2010 and 2019 bilateral ODA loans to LDCs grew 5-fold while grants were cut by 9%, and so it is likely this increase in ODA lending will mean more loans to countries with less ability to repay debt, which could lead to long term challenges, including constraints on domestic resources, as debt service consumes an ever larger proportion of government spending.

Overall, it is positive that donors stepped-up their contributions during the pandemic, however clearly more effort is needed if we are to ensure aid is allocated to populations and countries who need it most.

It is a critical resource particularly in times of crises, and more so in LDCs where it is the crucial source of external finance. However, the latest data shows these countries have seen much lower growth in support and there is a worrying rise on lending. There is work to do as donors turn their focus towards how we can rebuild in a post-covid world.

The OECD DAC’s most recent ODA data release is available here, and the full dataset can be accessed via OECD Stat.

For more detailed analysis of the 2020 OECD DAC’s ODA data preliminary release by Development Initiatives (DI) see DI’s factsheet here.

Category

News & ViewsThemes

UK aid